Iron Iii Oxide Balanced Equation

Iron O | |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name Iron(III) oxide | |

| Other names ferric oxide, haematite, ferric iron, red iron oxide, rouge, maghemite, colcothar, fe sesquioxide, rust, ochre | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number |

|

| 3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI |

|

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.790 |

| EC Number |

|

| Due east number | E172(ii) (colours) |

| Gmelin Reference | 11092 |

| KEGG |

|

| PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| InChI

| |

| SMILES

| |

| Properties | |

| Chemic formula | Fe two O 3 |

| Molar mass | 159.687 g·mol−one |

| Appearance | Scarlet-brown solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 5.25 m/cm3 [1] |

| Melting point | 1,539 °C (2,802 °F; 1,812 Grand)[one] decomposes 105 °C (221 °F; 378 Thou) β-dihydrate, decomposes 150 °C (302 °F; 423 Chiliad) β-monohydrate, decomposes 50 °C (122 °F; 323 G) α-dihydrate, decomposes 92 °C (198 °F; 365 K) α-monohydrate, decomposes[3] |

| Solubility in h2o | Insoluble |

| Solubility | Soluble in diluted acids,[1] barely soluble in saccharide solution[ii] Trihydrate slightly soluble in aq. tartaric acid, citric acid, CH3COOH[three] |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | +3586.0x10−vi cm3/mol |

| Refractive index (n D) | n1 = 2.91, n2 = 3.nineteen (α, hematite)[iv] |

| Structure | |

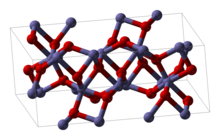

| Crystal construction | Rhombohedral, hR30 (α-course)[5] Cubic bixbyite, cI80 (β-class) Cubic spinel (γ-form) Orthorhombic (ε-form)[six] |

| Infinite group | R3c, No. 161 (α-form)[v] Ia3, No. 206 (β-form) Pna2one, No. 33 (ε-class)[6] |

| Point group | 3m (α-form)[5] 2/m 3 (β-form) mm2 (ε-grade)[half dozen] |

| Coordination geometry | Octahedral (Iron3+, α-form, β-form)[5] |

| Thermochemistry[seven] | |

| Heat capacity (C) | 103.ix J/mol·Yard[7] |

| Std tooth | 87.4 J/mol·K[7] |

| Std enthalpy of | −824.ii kJ/mol[7] |

| Gibbs free energy (Δf G ⦵) | −742.2 kJ/mol[seven] |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| Pictograms |  [8] [8] |

| Indicate word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H315, H319, H335 [8] |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P305+P351+P338 [8] |

| NFPA 704 (burn diamond) | [10] 0 0 0 |

| Threshold limit value (TLV) | 5 mg/mthree [1] (TWA) |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

| LDl (median dose) | 10 yard/kg (rats, oral)[x] |

| NIOSH (Us wellness exposure limits): | |

| PEL (Permissible) | TWA x mg/giii [ix] |

| REL (Recommended) | TWA v mg/thou3 [ix] |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 2500 mg/m3 [ix] |

| Related compounds | |

| Other anions | Atomic number 26(III) fluoride |

| Other cations | Manganese(Three) oxide Cobalt(III) oxide |

| Related iron oxides | Iron(Two) oxide Atomic number 26(II,III) oxide |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). Infobox references | |

Atomic number 26(III) oxide in a vial

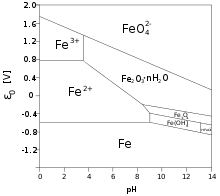

Iron(III) oxide or ferric oxide is the inorganic chemical compound with the formula Atomic number 26twoOiii. It is 1 of the three main oxides of iron, the other 2 being iron(II) oxide (FeO), which is rare; and atomic number 26(II,Three) oxide (Fe3O4), which as well occurs naturally equally the mineral magnetite. As the mineral known equally hematite, Fe2Oiii is the primary source of atomic number 26 for the steel industry. Fe2O3 is readily attacked by acids. Atomic number 26(III) oxide is ofttimes called rust, and to some extent this characterization is useful, considering rust shares several properties and has a similar composition; however, in chemistry, rust is considered an ill-defined material, described equally Hydrous ferric oxide.[11]

Structure [edit]

Fe2Oiii can be obtained in various polymorphs. In the main i, α, iron adopts octahedral coordination geometry. That is, each Atomic number 26 eye is spring to half-dozen oxygen ligands. In the γ polymorph, some of the Fe sit on tetrahedral sites, with four oxygen ligands.

Alpha phase [edit]

α-Fe2O3 has the rhombohedral, corundum (α-AliiO3) construction and is the most common form. It occurs naturally as the mineral hematite which is mined as the main ore of iron. Information technology is antiferromagnetic beneath ~260 Yard (Morin transition temperature), and exhibits weak ferromagnetism betwixt 260 1000 and the Néel temperature, 950 K.[12] Information technology is easy to set up using both thermal decomposition and precipitation in the liquid phase. Its magnetic backdrop are dependent on many factors, east.thousand. pressure level, particle size, and magnetic field intensity.

Gamma phase [edit]

γ-Fe2Othree has a cubic structure. It is metastable and converted from the blastoff stage at high temperatures. It occurs naturally as the mineral maghemite. It is ferromagnetic and finds application in recording tapes,[13] although ultrafine particles smaller than ten nanometers are superparamagnetic. It can be prepared past thermal dehydratation of gamma iron(Iii) oxide-hydroxide. Another method involves the careful oxidation of fe(Ii,3) oxide (Atomic number 26threeO4).[13] The ultrafine particles tin can be prepared by thermal decomposition of fe(Iii) oxalate.

Other solid phases [edit]

Several other phases have been identified or claimed. The β-stage is cubic trunk-centered (space group Ia3), metastable, and at temperatures to a higher place 500 °C (930 °F) converts to alpha stage. Information technology can be prepared by reduction of hematite by carbon,[ clarification needed ] pyrolysis of iron(Three) chloride solution, or thermal decomposition of atomic number 26(Iii) sulfate.[xiv]

The epsilon (ε) phase is rhombic, and shows backdrop intermediate between alpha and gamma, and may have useful magnetic properties applicative for purposes such as high density recording media for big information storage.[15] Preparation of the pure epsilon phase has proven very challenging. Material with a high proportion of epsilon stage tin exist prepared by thermal transformation of the gamma phase. The epsilon phase is besides metastable, transforming to the alpha phase at between 500 and 750 °C (930 and one,380 °F). It can also be prepared by oxidation of iron in an electrical arc or by sol-gel precipitation from iron(3) nitrate.[ citation needed ] Research has revealed epsilon iron(III) oxide in ancient Chinese Jian ceramic glazes, which may provide insight into means to produce that form in the lab.[16] [ not-primary source needed ]

Additionally, at high pressure an amorphous form is claimed.[vi] [ non-primary source needed ]

Liquid phase [edit]

Molten Atomic number 26twoOthree is expected to have a coordination number of close to v oxygen atoms about each fe atom, based on measurements of slightly oxygen scarce supercooled liquid fe oxide aerosol, where supercooling circumvents the need for the loftier oxygen pressures required above the melting signal to maintain stoichiometry.[17]

Hydrated iron(III) oxides [edit]

Several hydrates of Iron(III) oxide be. When alkali is added to solutions of soluble Fe(3) salts, a red-brown gelatinous precipitate forms. This is not Fe(OH)iii, but IroniiOthree·H2O (also written as Fe(O)OH). Several forms of the hydrated oxide of Atomic number 26(Iii) exist every bit well. The blood-red lepidocrocite (γ-Atomic number 26(O)OH) occurs on the outside of rusticles, and the orange goethite (α-Atomic number 26(O)OH) occurs internally in rusticles. When Atomic number 262Oiii·H2O is heated, it loses its water of hydration. Further heating at 1670 Yard converts Atomic number 26iiO3 to blackness Atomic number 263Ofour (FeIIIron3 2O4), which is known every bit the mineral magnetite. Fe(O)OH is soluble in acids, giving [Fe(H2O)6]3+ . In concentrated aqueous alkali, Atomic number 26twoO3 gives [Fe(OH)six]3−.[13]

Reactions [edit]

The most of import reaction is its carbothermal reduction, which gives fe used in steel-making:

- FeiiO3 + 3 CO → two Atomic number 26 + 3 CO2

Another redox reaction is the extremely exothermic thermite reaction with aluminium.[18]

- two Al + Fe2O3 → 2 Atomic number 26 + Al2Oiii

This process is used to weld thick metals such every bit runway of train tracks past using a ceramic container to funnel the molten iron in between 2 sections of rail. Thermite is also used in weapons and making pocket-size-calibration cast-fe sculptures and tools.

Partial reduction with hydrogen at about 400 °C produces magnetite, a black magnetic fabric that contains both Atomic number 26(III) and Iron(Ii):[xix]

- iii Atomic number 262O3 + Hii → two Fe3O4 + H2O

Iron(III) oxide is insoluble in h2o just dissolves readily in strong acid, e.g. hydrochloric and sulfuric acids. It also dissolves well in solutions of chelating agents such as EDTA and oxalic acrid.

Heating fe(III) oxides with other metal oxides or carbonates yields materials known every bit ferrates (ferrate (III)):[19]

- ZnO + Iron2Othree → Zn(FeO2)2

Training [edit]

Iron(III) oxide is a product of the oxidation of iron. It can be prepared in the laboratory past electrolyzing a solution of sodium bicarbonate, an inert electrolyte, with an iron anode:

- 4 Fe + 3 O2 + ii H2O → 4 FeO(OH)

The resulting hydrated iron(III) oxide, written here as FeO(OH), dehydrates around 200 °C.[19] [20]

- 2 FeO(OH) → Fe2O3 + HiiO

Uses [edit]

Fe manufacture [edit]

The overwhelming awarding of iron(Three) oxide is as the feedstock of the steel and iron industries, e.one thousand. the production of iron, steel, and many alloys.[20]

Polishing [edit]

A very fine powder of ferric oxide is known as "jeweler's rouge", "red rouge", or simply rouge. It is used to put the final shine on metallic jewelry and lenses, and historically as a corrective. Rouge cuts more than slowly than some modern polishes, such equally cerium(4) oxide, but is still used in optics fabrication and past jewelers for the superior finish it can produce. When polishing gilded, the rouge slightly stains the gold, which contributes to the advent of the finished slice. Rouge is sold every bit a powder, paste, laced on polishing cloths, or solid bar (with a wax or grease binder). Other polishing compounds are also frequently called "rouge", even when they exercise not contain iron oxide. Jewelers remove the residual rouge on jewelry by use of ultrasonic cleaning. Products sold as "stropping compound" are frequently applied to a leather strop to assist in getting a razor border on knives, straight razors, or any other edged tool.

Pigment [edit]

Two different colors at unlike hydrate phase (α: red, β: yellow) of atomic number 26(III) oxide hydrate;[3] they are useful as pigments.

Iron(3) oxide is also used as a pigment, nether names "Pigment Brown 6", "Pigment Brownish 7", and "Pigment Red 101".[21] Some of them, e.g. Pigment Ruby-red 101 and Pigment Brown six, are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in cosmetics. Atomic number 26 oxides are used every bit pigments in dental composites alongside titanium oxides.[22]

Hematite is the characteristic component of the Swedish paint color Falu crimson.

Magnetic recording [edit]

Iron(Three) oxide was the well-nigh common magnetic particle used in all types of magnetic storage and recording media, including magnetic disks (for information storage) and magnetic tape (used in sound and video recording too as information storage). Its use in figurer disks was superseded by cobalt alloy, enabling thinner magnetic films with higher storage density.[23]

Photocatalysis [edit]

α-Fe2O3 has been studied as a photoanode for solar water oxidation.[24] However, its efficacy is express by a short diffusion length (2–4 nm) of photo-excited charge carriers[25] and subsequent fast recombination, requiring a large overpotential to drive the reaction.[26] Research has been focused on improving the water oxidation performance of Fe2O3 using nanostructuring,[24] surface functionalization,[27] or by employing alternate crystal phases such as β-Fe2Oiii.[28]

Medicine [edit]

Calamine balm, used to care for balmy itchiness, is importantly composed of a combination of zinc oxide, acting as severe, and well-nigh 0.5% iron(Iii) oxide, the product's active ingredient, interim as antipruritic. The cerise color of iron(III) oxide is also mainly responsible for the balm's pink color.

Come across also [edit]

- Chalcanthum

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d Haynes, p. four.69

- ^ "A lexicon of chemical solubilities, inorganic". archive.org . Retrieved 17 Nov 2020.

- ^ a b c Comey, Arthur Messinger; Hahn, Dorothy A. (February 1921). A Dictionary of Chemic Solubilities: Inorganic (second ed.). New York: The MacMillan Company. p. 433.

- ^ Haynes, p. 4.141

- ^ a b c d Ling, Yichuan; Wheeler, Damon A.; Zhang, Jin Zhong; Li, Yat (2013). Zhai, Tianyou; Yao, Jiannian (eds.). One-Dimensional Nanostructures: Principles and Applications. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 167. ISBN978-ane-118-07191-v.

- ^ a b c d Vujtek, Milan; Zboril, Radek; Kubinek, Roman; Mashlan, Miroslav. "Ultrafine Particles of Atomic number 26(3) Oxides past View of AFM – Novel Route for Written report of Polymorphism in Nano-globe" (PDF). Univerzity Palackého . Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Haynes, p. five.12

- ^ a b c Sigma-Aldrich Co., Iron(Iii) oxide. Retrieved on 2014-07-12.

- ^ a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0344". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b "SDS of Iron(III) oxide" (PDF). KJLC. England: Kurt J Lesker Visitor Ltd. v January 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ PubChem. "Iron oxide (Fe2O3), hydrate". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov . Retrieved 11 Nov 2020.

- ^ Greedan, J. East. (1994). "Magnetic oxides". In King, R. Bruce (ed.). Encyclopedia of Inorganic chemistry. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN978-0-471-93620-half dozen.

- ^ a b c Housecroft, Catherine E.; Sharpe, Alan G. (2008). "Chapter 22: d-block metallic chemistry: the first row elements". Inorganic Chemical science (3rd ed.). Pearson. p. 716. ISBN978-0-13-175553-6.

- ^ "Mechanism of Oxidation & Thermal Decomposition of Iron Sulphides" (PDF).

- ^ Tokoro, Hiroko; Namai, Asuka; Ohkoshi, Shin-Ichi (2021). "Advances in magnetic films of epsilon-iron oxide toward next-generation high-density recording media". Dalton Transactions. Regal Lodge of Chemistry. 50 (2): 452–459. doi:10.1039/D0DT03460F. PMID 33393552. S2CID 230482821. Retrieved 25 Jan 2021.

- ^ Dejoie, Catherine; Sciau, Philippe; Li, Weidong; Noé, Laure; Mehta, Apurva; Chen, Kai; Luo, Hongjie; Kunz, Martin; Tamura, Nobumichi; Liu, Zhi (2015). "Learning from the past: Rare ε-Atomic number 262O3 in the ancient black-glazed Jian (Tenmoku) wares". Scientific Reports. 4: 4941. doi:ten.1038/srep04941. PMC4018809. PMID 24820819.

- ^ Shi, Caijuan; Alderman, Oliver; Tamalonis, Anthony; Weber, Richard; Yous, Jinglin; Benmore, Chris (2020). "Redox-structure dependence of molten iron oxides". Communications Materials. 1 (1): fourscore. Bibcode:2020CoMat...1...80S. doi:x.1038/s43246-020-00080-4.

- ^ Adlam; Price (1945). College School Certificate Inorganic Chemical science. Leslie Slater Price.

- ^ a b c Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry, second Ed. Edited by G. Brauer, Academic Printing, 1963, NY. Vol. 1. p. 1661.

- ^ a b Greenwood, Northward. Northward.; Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemical science of the Element (2nd ed.). Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN978-0-7506-3365-9.

- ^ Paint and Surface Coatings: Theory and Practice. William Andrew Inc. 1999. ISBN978-1-884207-73-0.

- ^ Banerjee, Avijit (2011). Pickard's Transmission of Operative Dentistry. Us: Oxford University Press Inc., New York. p. 89. ISBN978-0-19-957915-0.

- ^ Piramanayagam, S. N. (2007). "Perpendicular recording media for hard disk drive drives". Periodical of Applied Physics. 102 (ane): 011301–011301–22. Bibcode:2007JAP...102a1301P. doi:ten.1063/1.2750414.

- ^ a b Kay, A., Cesar, I. and Grätzel, Grand. (2006). "New Benchmark for Water Photooxidation by Nanostructured α-Fe2O3 Films". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (49): 15714–15721. doi:10.1021/ja064380l. PMID 17147381.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors listing (link) - ^ Kennedy, J.H. and Frese, Thousand.W. (1978). "Photooxidation of Water at α-Iron2O3 Electrodes". Journal of the Electrochemical Social club. 125 (v): 709. doi:10.1149/ane.2131532.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Le Formal, F. (2014). "Back Electron–Hole Recombination in Hematite Photoanodes for Water Splitting". Journal of the American Chemic Society. 136 (6): 2564–2574. doi:10.1021/ja412058x. PMID 24437340.

- ^ Zhong, D.Grand. and Gamelin, D.R. (2010). "Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation by Cobalt Goad ("Co−Pi")/α-Iron2O3 Composite Photoanodes: Oxygen Evolution and Resolution of a Kinetic Clogging". Journal of the American Chemical Order. 132 (12): 4202–4207. doi:10.1021/ja908730h. PMID 20201513.

{{cite periodical}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Emery, J.D. (2014). "Atomic Layer Degradation of Metastable β-FeiiO3 via Isomorphic Epitaxy for Photoassisted Water Oxidation". ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. vi (24): 21894–21900. doi:x.1021/am507065y. OSTI 1355777. PMID 25490778.

External links [edit]

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

Iron Iii Oxide Balanced Equation,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iron(III)_oxide

Posted by: potterrapen1954.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Iron Iii Oxide Balanced Equation"

Post a Comment